There is an ever-increasing focus on climate change and corresponding changes to rainfall patterns. It seems like more extreme rainfall events are observed every year. Wisconsin and Minnesota Discovery Farms Programs have monitored 127 site years of edge-of-field surface runoff. During these site years, 2,184 surface runoff events were measured. These runoff events and the corresponding rainfall data were analyzed to answer the following questions:

- Are a large portion of nutrient and soil losses driven by extreme rainfall events?

- Can you control the weather (or the impact of it) on your crop fields?

Most nutrient and soil losses happened in a limited number of runoff events.

The majority of the nutrient and soil losses happened in about 200 of the 2,184 runoff events. The top 10% of surface runoff events accounted for 46% of the total runoff, 59% of the total nitrogen, 65% of the total phosphorus, and 80% of the total soil lost throughout the entire dataset.

Most runoff events took place during storms of an ‘expected’ size, not extreme events.

All the surface runoff events were paired with rainfall data, including depth, duration, intensity, and maximum 5, 10, 30 and 60-minute intensities. Intensity data was then compared with NOAA data from each location to define rainfall return periods for each runoff event.

A rainfall return period is an estimate of the likelihood of a rainfall event to occur. In general, as the return period increases, so does the rainfall or rainfall intensity.

- A rainfall event with a 100-year return period would be expected to occur once in 100 years.

- The probability of a 100-yr rainfall event occurring in any given year is 1/100 or 1%.

Out of 2,184 total runoff events from 127 site years of data, there were 375 runoff events with a rainfall return period greater than one year. There were 11 runoff events with a rainfall return period of greater than 25 years and four with a rainfall return period estimated to be greater than 1,000 years.

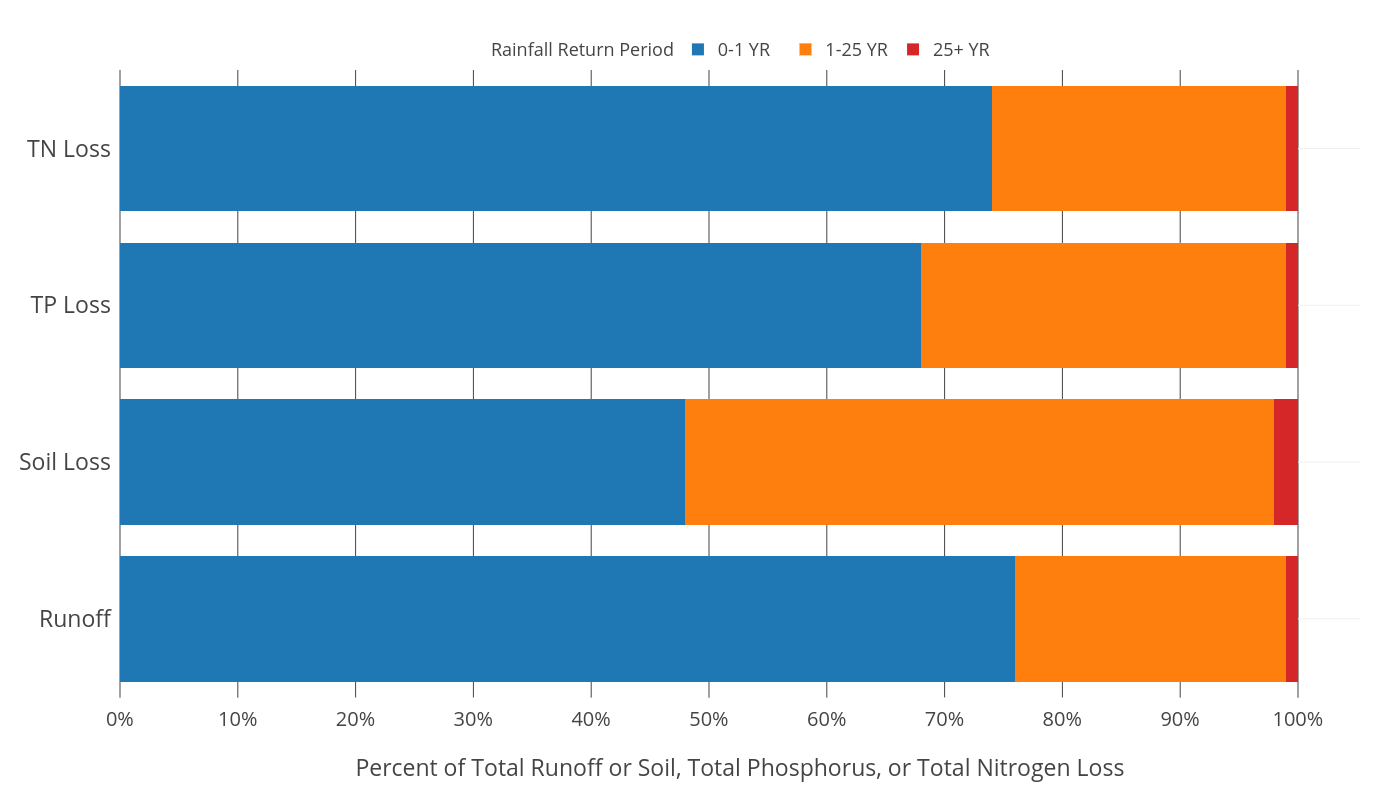

Extreme rainfall events did not significantly impact edge-of-field nutrient losses. 70-75% of surface runoff, total phosphorus, and total nitrogen losses were NOT driven by extreme rainfall.

Most of the surface runoff, total phosphorus, and total nitrogen losses were from surface runoff events that had rainfall return periods of less than one year (see blue bar on graph). This means these runoff events resulted from common rainfall events or snowmelt. However, over 50% of the soil loss happened with runoff events with a rainfall return period greater than one year. Extreme rainfall events had more of an impact on soil loss.

Often a 25-year rainfall event is used as design criterion for conservation practices in agricultural fields. Surface runoff with a rainfall return period of greater than 25 years had very little influence (1 to 2%) on surface runoff losses in this dataset. This could be a result of effective conservation practices designed to withstand larger rainfall events or the relatively few 25-year rainfall events that have been monitored. In fact, only 11 surface runoff events had a rainfall return period greater than 25 years.

Timing of extreme rainfall matters.

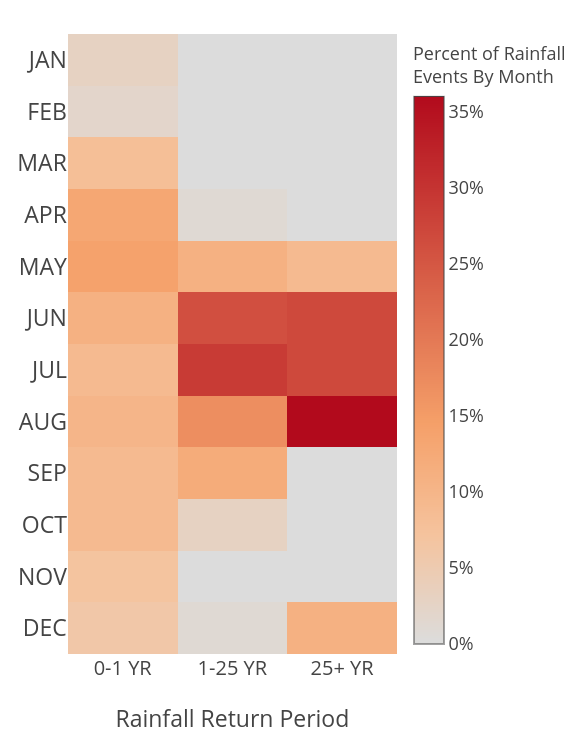

An extreme rainfall event in April or May will have a different surface runoff response than an extreme rainfall event in July or August. This is largely because of a difference in crop cover for annual crops. In April and May, there is limited crop cover and soil protection. This period also tends to have wetter soils because of the lack of plant growth and transpiration. Annual crops are usually fully canopied by July and August, providing great cover and soil protection. Soils are also typically drier during this period because of the greater water use by a fully canopied crop.

Most of the extreme rainfall events in this dataset were in June, July and August. June is a transition month where the annual crops typically move to fully canopied fields, but July and August are periods that will provide more protection. If the timing of these extreme rainfall events were to shift to earlier in the year, the surface runoff influence would likely increase.

Snowmelt is still a significant part of the water budget and decreases the influence of extreme rainfall events in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Over half of the surface runoff measured in Minnesota and Wisconsin occurred during frozen soils and snowmelt conditions. This is an important period for runoff in the Upper Midwest. This period is also important for phosphorus and nitrogen movement. However, soil movement is limited during snowmelt. The amount of snowmelt runoff and nutrient losses diminishes the impact of extreme rainfall events. If runoff and nutrient loss occurring with snowmelt decreases, it would likely increase the influence of extreme rainfall events.

Takeaways to consider from this analysis:

- Most surface runoff losses happen in a limited number of runoff events.

- Extreme rainfall events did not significantly impact edge-of-field losses except for soil loss.

- Timing of extreme rainfall events matter. If extreme events occur earlier in the year it would likely increase their impact on surface runoff.

- Snowmelt is still a large driver and decreases the influence of extreme rainfall events in WI and MN.

- There is a need for a site-by-site assessment to explore differences by region, soil type and level of conservation practices.

This article originally appeared in the latest UW Discovery Farms newsletter. If you would like to read more from the newsletter please click here.

- Lessons Learned from Schafer Farms – Implementing Conservation in a Rolling Landscape - April 8, 2020

- What happened to spring? - July 15, 2019

- Tile flow and nutrient movement in Northwest Minnesota - September 13, 2018